Insurance Is a Mechanism for Protection Agains

Abstract

We examine mechanisms as to why insurance and individual risk reduction activities are complements instead of substitutes. We use data on flood risk reduction activities and flood insurance purchases by surveying more than 1000 homeowners in New York City after they experienced Hurricane Sandy. Insurance is a complement to loss reduction measures undertaken well before the threat of suffering a loss, which is the opposite of a moral hazard effect of insurance coverage. In contrast, insurance acts as a substitute for emergency preparedness measures that can be taken when a loss is imminent, which implies that financial incentives or regulations are needed to encourage insured people to take these measures. We find that mechanisms leading to preferred risk selection are related to past flood damage and a crowding out effect of federal disaster assistance as well as behavioral motivations to reduce risk.

Introduction

Seminal theoretical papers highlight that insurance and risk reducing protective measures are substitutes (Ehrlich and Becker 1972; Arnott and Stiglitz 1988). According to the theory, insurance would discourage individuals from investing in loss reduction measures unless they are rewarded with a reduction in their premiums. This behavior may lead to moral hazard when individuals take fewer risk-reducing measures after purchasing insurance, and to adverse selection when it is mainly individuals with a high risk who demand insurance but the insurer cannot distinguish between high and low risk individuals. These two problems arise from information asymmetries in the sense that the higher risk-taking by the insured is not observed by the insurer and, therefore, not reflected in a higher risk based premium (Akerlof 1970; Rothschild and Stiglitz 1976).

Recent work over the past decade reveals that some insured individuals may view additional measures to limit risk ex ante as complements to insurance and thus implement more of these measures than the uninsured do, for example, because they are (highly) risk averse. This behavior can lead to both insurance purchases and investments in risk reduction; this has been termed advantageous selection (de Meza and Webb 2001) or preferred risk selection (Finkelstein and McGarry 2006). Finkelstein and McGarry (2006) find that individuals with private long term care insurance in the United States are more likely to engage in activities that reduce health risks, which in turn makes it less likely that they will ever use long-term care. Cutler et al. (2008) also show that positive relationships exist between individuals in the United States purchasing term life, annuities, medigap and long term care insurance and adopting risk reduction activities. The datasets used in these studies do not allow for examining the exact behavioral mechanisms behind the observed preferred risk selection, though.

Other empirical research has also shown that there can be significant heterogeneity in the relation between insurance coverage and risk reduction (Cohen and Siegelman 2010). Einav et al. (2013) found that some individuals who engage in moral hazard have a higher demand for health insurance coverage, except for highly risk averse individuals with a high perceived health risk who do not engage in moral hazard and have a high willingness-to-pay for insurance coverage. The lack of empirical evidence on adverse selection in some insurance markets may be consistent with the hypothesis that buyers are not maximizing their expected utility, but it is also consistent with the hypothesis that little information asymmetry exists.

In this paper we examine the relationship between individual risk reduction activities and natural disaster insurance coverage as our field case by identifying behavioral mechanisms that may explain preferred risk selection. In particular we use the U.S. flood insurance market and the decisions by homeowners to reduce flood risk by investing in loss reduction measures as our context. Floods are the most costly source of natural disasters in the U.S., Footnote 1 and there is an expectation that the frequency and severity of flooding will increase in the future as a result of climate change and the accompanying sea level rise (IPCC 2014). Flood insurance for residential properties is almost exclusively purchased through the federally-run National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which covers more than $1.2 trillion of assets. This makes the NFIP the largest flood insurance program worldwide.

We make a temporal distinction between risk reduction activities that are normally adopted well before the risk (i.e. a flood disaster) materializes, such as dry proofing walls of a building to make them impermeable to water, and emergency preparedness measures that are undertaken during an imminent threat of a disaster, such as moving contents to higher floors to avoid them suffering flood damage. Loss reduction measures often have a high upfront cost with an uncertain benefit, while emergency preparedness measures are generally less costly and have more certain risk reduction benefits.

Recent experiences with low-probability/high-impact events have given rise to an increasing interest in the economics literature in how people prepare for, and respond to, disasters (Barberis 2013). In particular, Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Hurricane Sandy in 2012, which combined caused more than $150 billion in economic losses in the United States, showed the importance of undertaking protective measures to reduce future disaster damage (Munich Re 2015). Moreover, such disasters highlight the need to provide recovery funds through insurance should one suffer losses from a disaster and to find ways to improve disaster preparedness in the future.

Only a handful of studies have examined the relationship between investment in risk reduction and insurance purchase decisions for natural disasters (for a review see Hudson et al. 2017). Carson et al. (2013) show that homeowners in Florida who have high deductibles on their windstorm insurance are also more likely to take windstorm risk reduction measures. This suggests that insurance coverage and wind risk reduction measures act as substitutes, at least in terms of the deductible amount. On the other hand, Petrolia et al. (2015) find a positive relation between the decision to purchase windstorm coverage and investment in measures that limit windstorm damage based on a sample of U.S. households along the Gulf coast. A follow-up study by Hudson et al. (2017) using a different U.S. sample from the mid-Atlantic and Northeastern U.S. revealed that households with homeowner's or flood insurance that are threatened to be hit by a hurricane are also more likely to engage in activities that minimize windstorm risks. With respect to flood risk, Thieken et al. (2006) and Hudson et al. (2017) find that insured households in Germany take more flood risk mitigation measures than households without flood insurance. These studies, however, did not identify the behavioral mechanisms behind the relations between insurance and risk reduction activities, which we aim to do here.

Our study uses data from a survey we conducted of more than 1000 homeowners who live in flood-prone areas in New York City (NYC). This dataset includes individual level information on implemented flood risk reduction measures and flood insurance purchases from the NFIP as well as a range of variables that influence these decisions, such as psychological characteristics, risk perceptions, experience of past flood damage and receipt of federal disaster assistance. Our individual level data is especially suitable for determining whether the relationship between insurance purchase and risk reduction activities by individuals are substitutes or complements, and for identifying the behavioral mechanisms behind these relationships.

The NFIP regulates development in the 1 in 100 year flood zone via specific elevation requirements and by restricting new construction in floodways (Aerts and Botzen 2011; Dehring and Halek 2013). Here we focus on voluntary flood risk reduction measures that households can undertake to prevent flood water from entering a building or to minimize damage once water has entered the structure. These flood-proofing measures can be especially attractive for existing structures that are very expensive to elevate. Cost-benefit analyses have shown that elevation can be cost-effective for new structures, but not for existing buildings (Aerts et al. 2014).

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the data and the empirical methods. Section 3 presents the results. We find that insurance and long-term risk reduction measures taken ex ante a flood threat are complements, which is opposite to a moral hazard effect. In contrast, we find that people with insurance coverage are less likely to take short-term emergency preparedness measures during a flood threat. An examination shows that individuals both insure and take risk reduction measures for financial reasons, like experiencing high flood damage in the past and not having received federal disaster assistance for damage. Interestingly, we find that behavioral motivations to reduce risk outside of the standard economic model also play a role. Section 4 concludes and provides policy recommendations.

Data and empirical methods

The databases Footnote 2 of our survey consists of a random sample of homeowners in NYC that face flood risk who live in a house with a ground floor. This means that renters and those living in apartments above the ground floor level are not included in our sample. The survey was implemented over the phone by a professional survey company about six months after NYC was flooded by Superstorm Sandy in October 2012. 1035 respondents completed the survey (73% completion rate). See the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) for more details about the survey method and survey questions. We use probit models of (flood) insurance purchases and explanatory variables of flood risk reduction activities to examine the relationship between flood insurance purchases and flood risk reduction measures. Treating the purchase of insurance as a dependent variable is consistent with related research that examines the relationship between insurance coverage and risk reduction by policyholders in the context of health risks (e.g. Finkelstein and McGarry 2006; Cutler et al. 2008) and natural hazard risks (Hudson et al. 2017). Voluntarily purchasing flood insurance is a personal decision that is made annually and can be cancelled at any time, which also justifies having it as the dependent variable. Most flood risk mitigation measures are long-term adjustments to the structure of a home, with some being implemented by a previous owner of the house. On the other hand, some are a temporary response to a known threat, such as emergency preparedness measures. This is why we also estimate models with implemented flood risk mitigation measures as the dependent variable and insurance and other relevant factors as explanatory variables, to examine if the main results for our main hypotheses are robust to this alternative specification.

Our basic probit models are:

$$ Y\ {\left( mandatory\ insurance\right)}_i={\beta}_1+{\alpha}_1{M}_i+{\varepsilon}_{1,i} $$

(1)

$$ Y\ {\left( voluntary\ insurance\right)}_i={\beta}_2+{\alpha}_2{M}_i+{\varepsilon}_{2,i} $$

(2)

where Y i is a binary variable indicating whether respondent i has flood insurance (Y i = 1) or no flood insurance at all (Y i = 0), Footnote 3 M i are variables of implemented risk reduction measures. Two empirical models are estimated for the subgroups for which (Y i = 1) since some individuals are required to have flood coverage (1) if they have a federally insured mortgage and live in a designated high-risk flood zone (the 1 in 100 year flood zone defined by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)), while others purchase it voluntarily (2). The relationship between insurance coverage and risk reduction may differ between people who bought flood insurance voluntarily or mandatorily, which is why we make this distinction. The mandatory insurance model also enables us to determine whether homeowners who are required to purchase flood insurance implement more or fewer risk reduction measures than those who are uninsured. M i consists of two separate variables of the number of implemented ex ante risk reduction measures at the household level (i.e. structural measures implemented in the home to limit flood damage) and emergency preparedness measures (which also limit flood damage but require a behavioral response of the homeowner in the immediate time period before the flood occurs).

We make a distinction between these two types of protective measures throughout our analysis because decision processes of taking these measures are likely to be different. Risk reduction measures taken ex ante a flood threat have relatively high upfront costs with uncertain risk reduction benefits that materialize if a flood occurs. Emergency preparedness measures taken during a flood threat, like moving contents to higher floors and installing flood shields, are often relatively less expensive, but require the household to take action in a situation of emergency when the likelihood of a flood occurring is now almost certain. We specify two hypotheses (H1 and H2) depending on whether coefficients α 1 and α 2 are negative, pointing toward households' viewing insurance and risk reduction measures as substitutes (H1) or whether these coefficients are positive, revealing that these measures are viewed as complements (H2). Although our research design cannot directly prove causality between insurance and risk reduction measures, evidence supporting H1 is consistent with a moral hazard effect, while evidence supporting H2 is consistent with a preferred risk selection effect.

Estimating Eqs. (1) and (2) provides insights into how the insurance purchase decision is related with investments in loss prevention. To examine how other variables influence the decision to buy insurance and potentially affect the relationship between Y i and M i , two other models are estimated: a traditional economic model and a behavioral economic model, respectively.

The traditional economic model is:

$$ Y\ {\left( mandatory\ insurance\right)}_i={\beta}_1+{\alpha}_1{M}_i+{\gamma}_1{R}_i+{\varphi}_1{F}_i+{\delta}_1{X}_i+{\varepsilon}_{1,i} $$

(3)

$$ Y\ {\left( voluntary\ insurance\right)}_i={\beta}_2+{\alpha}_2{M}_i+{\gamma}_2{R}_i+{\varphi}_2{F}_i+{\delta}_2{X}_i+{\varepsilon}_{2,i} $$

(4)

The following new variables are introduced in Eqs. 3 and 4: R i reflects either homeowners risk perceptions (model variants 3a and 4a) or experts estimates of the flood risk (model variants 3b and 4b), F i characterizes federal disaster assistance received by homeowner i, and X i are socio-demographic variables, including income which we capture by including dummy variables of four categories of total household income of which the coefficients show the effects on insurance purchases versus the excluded dummy variable of the very high income category (>$125,000). Those required to purchase flood insurance reside in areas designated by FEMA to have a higher flood risk than those having the option to buy coverage. A principal reason for distinguishing between these two groups is determining whether their relationship between having flood insurance coverage and investing in risk reduction measures (Mi) differ as well as whether their perceptions of the risk and those of the experts differ in their insurance purchase decision.

Definitions and coding of all variables are provided in ESM Table 1. If a question was not answered by a respondent, then this resulted in missing observations for the variable that is based on this question. This implies that the number of observations in our statistical models varies dependent on the number of non-missing observations for the explanatory variables included in that model. Footnote 4

R i are either variables of risk perception measured as perceived flood probability and consequences in line with subjective expected utility theory (Savage 1954) or expert estimates of these variables. These expert indicators of flood risk faced by the respondents have been derived from a probabilistic flood risk model developed for NYC. A detailed description of this model and all flood modelling results can be found in Aerts et al. (2014, including online material). Based on a large set of 549 simulated hurricanes from a coupled hurricane hydro-dynamic model (Lin et al. 2012) the probability that the property of each survey respondent will experience inundation from a flood has been derived (Aerts et al. 2014). An indicator of flood damage was calculated for each respondent based on the mean expected flood inundation level at the respondent's location and the value of a respondent's property that are input to a depth-damage function for each specific building category derived from the HAZUS-MH4 methodology (HAZUS stands for Hazards United States). Such depth-damage curves are commonly used in flood risk assessments, and represent the fraction of a building and its content value that is lost in a flood based on the flood water level present in the census block (Aerts et al. 2013, 2014).

F i is a dummy variable representing respondents who have received federal disaster assistance for flood damage in the past. They may expect the government to compensate them for damage suffered from a future flood, which can lower their demand for insurance and risk reduction measures. This crowding out effect has been called the Samaritan's dilemma or charity hazard (Buchanan 1975; Browne and Hoyt 2000; Raschky et al. 2013). The traditional economic model is also estimated for mandatory flood insurance purchases, because budget constraints due to low income and the receipt of federal disaster assistance in the past may be reasons for not adhering to the mandatory purchase requirements of the NFIP.

Next, a behavioral economic model is estimated to examine factors and motivations that are likely to lead to purchasing insurance voluntarily:

$$ Y\ {\left( voluntary\ insurance\right)}_i={\beta}_1+{\alpha}_1{M}_i+{\gamma}_1{T}_i+{\varphi}_1{F}_i+{\delta}_1{X}_i+{\mu}_1{B}_i+{\varepsilon}_{1,i} $$

(5)

Variables M i , F i and X i are similar to those for Eq. 4. A difference in (5) is that R i in (4) is now represented by T i which is a variable indicating respondents who think that the flood probability is below their threshold level of concern. This variable is included since other studies have found that individuals may use a threshold model in assessing low-probability/high-impact risk (Slovic et al. 1977; McClelland et al. 1993; Kunreuther et al. 2001; Botzen et al. 2015). This model implies that many individuals choose not to insure because they ignore the flood risk. B i consists of behavioral variables that examine whether individuals purchase insurance because it gives them peace of mind, and whether their decision to purchase coverage is affected by their locus of control, their own internal values or a social norm.

The peace of mind variable is included because affect and emotion-related goals appear to have an important influence on decision making under risk (Loewenstein et al. 2001). Individuals may purchase insurance to reduce anxiety, and to avoid anticipated regret not to have bought it should a disaster happen and consolation (Krantz and Kunreuther 2007), which is captured by this variable.

Locus of control is a personality trait which reflects a belief about the degree to which an individual exerts control over his or her own life, in contrast to external environmental factors, such as fate or luck (Rotter 1966). It has been shown that locus of control influences economic decision making in various domains such as earnings (Heineck and Anger 2010), entrepreneurship (Evans and Leighton 1989), investments in education (Coleman and Deleire 2003) and in health (Chiteji 2010). It can be expected that individuals with an external locus of control Footnote 5 think they have little influence over outcomes in their life and are less likely to prepare for disasters and purchase flood insurance (Baumann and Sims 1978; Sattler et al. 2000).

Moreover, norms may be a motivation for people to prepare for disasters, as has been shown for the influence of norms on other economic decisions, like consumption, work effort, and cooperation in public good provision, and perceived fairness of income distributions and uses of (public) money, as reviewed by Elster (1989). Being adequately prepared for a specific risky situation may be regarded as a social norm, so that households do not need to rely on others for assistance during and after a disaster. In another context, namely recycling decisions by individuals, Viscusi et al. (2011) and a more detailed follow up study by Huber et al. (2017) show that it is important to distinguish between a person's behavior due to the actions of others (i.e. social norms) and private values. We realize that recycling decisions can follow a different behavioral process than flood preparedness decisions, but the relevance of distinguishing between different types of social norms has been found in a variety of contexts such as littering and energy savings (see the review in Huber et al. 2017). Whether private values are stronger predictors of behavior than social norms may depend on the type of decision. Since in principle, both social norms and private values may be positively related to taking flood risk reduction measures and purchasing flood insurance, we examine the influence of both variables. Footnote 6 In our study, a social norm refers to approval of others of being well prepared for flooding, while a private value refers to behavior that the respondent finds to be personally important. Footnote 7

Furthermore, we estimate two variants of (5) which include interaction terms with ex ante risk reduction measures in order to examine how behavioral and financial mechanisms relate to the adoption of both risk reduction measures and purchase of insurance. First, we examine how the behavioral characteristics B i influence the decision to both purchase flood insurance and adopt risk reduction measures by creating interactions terms of these Bi variables with the ex ante risk reduction variable. In particular, the norm and locus of control variables can reflect internal preferences of the individual with regard to risk preparedness which may affect decisions to both insure and implement risk reduction measures. Second, a model is estimated to examine how the interaction between risk reduction and flood insurance purchases is related to financial incentives through previous flood damage and past federal disaster assistance. Experiencing severe flood damage may trigger the adoption of ex ante risk reduction measures and the purchase of insurance when individuals perceive that insurance coverage alone is insufficient for coping with future flood events. Individuals who have received federal disaster assistance may expect the federal government to cover their future losses. They therefore are less likely to invest in risk reduction measures and purchase insurance than if they believed they would be responsible for the costs of repairing their damage after a disaster.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Of our total number of respondents, 44% purchased flood insurance because doing so was mandatory, 21% purchased it voluntarily, 33% did not have flood insurance and 2% did not know whether they had flood coverage.

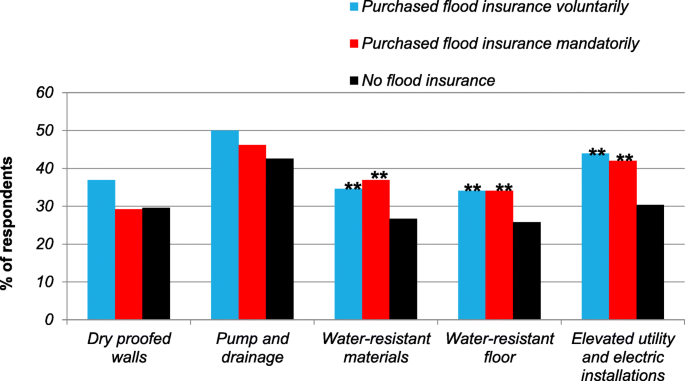

Figure 1 shows the relation between having flood insurance coverage and the implementation of specific (structural) risk reduction measures, which are taken ex ante a flood threat. These measures often have substantial upfront investment costs and limit damage during flood events. If insurance and risk reduction measures are substitutes then one would expect that individuals with flood insurance coverage would undertake fewer risk reduction measures than individuals without flood insurance, because FEMA does not give premium discounts for policyholders who adopt such measures. The one exception is if a homeowner elevates his home and therefore this measure is not considered in our analysis. Footnote 8 As shown in Fig. 1, individuals who voluntarily and mandatorily purchased flood insurance are also more likely to take ex ante risk reduction measures than the uninsured, which is statistically significant for building with water-resistant materials, having a water-resistant floor, and elevating utility and electric installations.

Percentage of respondents who implemented specific ex ante risk reduction measures for individuals who purchased flood insurance voluntarily, mandatorily or not at all. Note: ** indicates a significant difference at the 5% level with the no flood insurance group

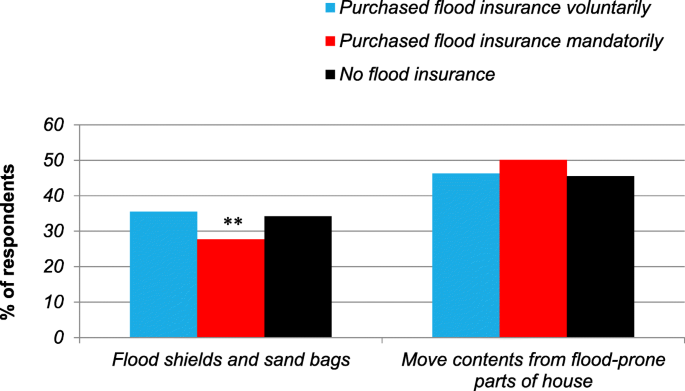

This (positive) relationship between having flood insurance coverage and undertaking flood risk reduction measures is less clear for emergency preparedness measures such as moving contents to a higher floor (Fig. 2). Compared with the uninsured, individuals with mandatory flood insurance are statistically significantly less likely to place flood shields and sandbags to limit damage during a flood, while they are slightly more likely to move home contents away from flood-prone parts of the house, but this relationship is insignificant. The percentage of people with voluntary and no flood insurance coverage taking these measures is similar and does not differ significantly from actions taken by individuals who are uninsured.

Percentage of respondents who implemented specific emergency preparedness measures for individuals who purchased flood insurance voluntarily, mandatorily or not at all. Note: ** indicates a significant difference at the 5% level with the no flood insurance group

Results of statistical models

The results of simple probit models (Eqs. 1 and 2) of relations with insurance purchases and risk reduction measures are shown in ESM Table 2. The results confirm the positive significant relation with (mandatory and voluntary) flood insurance purchases and ex ante risk reduction measures, while the coefficient of emergency preparedness measures is negative, albeit insignificant. This negative coefficient is due to the controlling for implemented risk reduction measures. A separate probit model with only emergency preparedness measures yields a positive (insignificant) coefficient for this variable, which becomes negative in a model when risk reduction measures are included as explanatory variable. Footnote 9

Table 1 shows the results of probit models of flood insurance purchases with explanatory variables motivated by a traditional economic model of decision making under risk (Eqs. 3 and 4). Our main interest here is to measure the relation between insurance coverage and the adoption of risk reduction activities. A consistent picture emerges in both models: individuals with flood insurance coverage are more likely to have invested in measures that flood-proof their building ex ante a flood threat (positive and significant marginal effect). The probit model in Table 1 also finds a significant negative relation between having insurance and undertaking emergency preparedness measures shortly in advance or during flood events, while this negative effect was statistically insignificant in the simple model without control variables (Eqs. 1 and 2, shown in ESM Table 2).

In other words, while accounting for standard economic explanatory variables that influence insurance purchases, individuals with that coverage are less likely to have flood shields or sand bags available or move contents out of flood-prone parts of their house. This points towards a moral hazard effect, at least for emergency preparedness measures which are generally taken just before a flood occurs, or even as it does occur. The opposite relationships with insurance coverage for longer term risk reduction measures and shorter term emergency preparedness measures indicate that the decision processes of taking long-term vs. short-term disaster preparedness measures differ.

The flood risk faced by the respondent could be an influencing factor on both decisions to purchase flood insurance and undertake damage mitigation measures. The perceived flood probability Footnote 10 is positively related to mandatory purchases, but this effect is not very strong (p value<0.1), while it is insignificant in the model of voluntary flood insurance purchases. The perceived flood damage is insignificant in both models of mandatory and voluntary flood insurance purchases. Footnote 11 Models 3b and 4b in Table 1 include experts estimates of the flood probability Footnote 12 and expected flood damage instead of the perceived flood probability and perceived flood damage. The expert flood probability has an insignificant effect on voluntary flood insurance purchases, while the mandatory flood insurance coverage is positively related to experts estimates of the flood probability. This is to be expected since mandatory purchase requirements are required only in FEMA high risk zones for which flood probabilities are high. The expert flood damage only has a significant effect on voluntary flood insurance purchases which suggests that individuals in lower risk areas purchase insurance coverage because they focus on potential losses, while those in high risk areas don't think about the damage because they are required to buy coverage. These findings that hazard severity plays a larger role in voluntary flood insurance demand than hazard probability are in line with research showing that many individuals do not seek or use probabilistic information in making decisions (e.g. Kunreuther et al. 2001). The main relations between flood risk mitigation activities and flood insurance coverage are similar when perceptions or objective indicators of the flood probability and consequences are included as explanatory variables.

Another important finding is that households who have received federal disaster assistance to compensate for uninsured flood damage suffered in the past are less likely to carry both mandatory and voluntary flood insurance. Footnote 13 This is not necessarily what we expected a priori. On the one hand, households without flood coverage who claimed compensation from federal assistance are required to carry flood insurance. On the other hand, if households expect that the government will bail them out again during a future flood event, they may drop this coverage again which would be a typical charity hazard effect. We find that the latter effect dominates. The marginal effect of this variable is rather large; the probability of having flood insurance is between 0.1 and 0.2 lower after receiving disaster relief. A variable of having received disaster assistance but in the form of a loan turned out to be statistically insignificant (not shown in Table 1), suggesting that compensations through loans are not a substitute for insurance, which confirms early results by Kousky et al. (2013).

A significant income effect is present for flood insurance purchases. A dummy variable of households with a very low total household income (<$25,000) is statistically significant in the models of voluntary purchases, which means that these individuals are less likely to buy flood coverage than those with a very high income (the excluded baseline) due to affordability concerns. A significant lower purchase of mandatory insurance is also observed for people with a low income. For individuals with a very low income and middle high income a significant effect appears only in model 3b. Overall our findings imply that concerns about insurance affordability in addressing the pricing of flood insurance and providing financial assistance to incentivize purchase of coverage and investments in cost-effective mitigation measures need to be considered (Kousky and Kunreuther 2014). Voluntary insurance purchases are positively related with having a high education level. Footnote 14 These results for socio-economic variables suggest that more vulnerable social groups with a low income and low education level are less likely to purchase flood insurance, and, thereby, have worse financial protection against flood damage.

Next, we examine in more detail the behavioral motivations for voluntarily purchasing insurance and for combining this insurance coverage with risk reduction measures. Table 2 shows the results of a model with explanatory variables that are motivated by a range of behavioral economic theories that postulate that individuals base decisions under risk on intuitive thinking and other psychological decision processes (Eq. 5). In particular, the model includes a threshold variable of perceived risk that represents respondents who think that the probability their house will suffer a flood is below their threshold level of concern, and variables of a private value of preparing for flooding, individual locus of control, and purchasing flood insurance because it gives peace of mind. Moreover, we examined whether in addition to these variables, flood experience Footnote 15 significantly influences voluntary flood insurance purchases. This did not turn out to be the case (results not shown in Table 2), which may be due to the large share of our respondents (about 75%) that had been flooded in the past.

The main relations between flood risk mitigation activities and flood insurance coverage are similar when the aforementioned behavioral variables are included in the model. The behavioral economic model provides some important additional insights, though, compared to the standard economic models. Individuals who think that the flood probability is below their threshold level of concern are less likely to purchase flood insurance (p value = 0.06). Individuals with an external locus of control who think they have little control about outcomes in their life are less likely to demand flood insurance. Moreover, flood insurance demand is positively related to a strong private value Footnote 16 of being well prepared for flooding (see the survey question in footnote 7). A separate model was estimated including the external social norm variable (not shown here), which turned out to have an insignificant effect on voluntary flood insurance purchases. This is in line with findings from Viscusi et al. (2011) and Huber et al. (2017) who show that recycling behavior in the United States is influenced by private values and not external social norms, and conclude that it is important to distinguish these two types of variables as we do here. Moreover, we find that peace of mind is an important motivation for individuals to purchase flood insurance. About 70% of the respondents indicated that they were similar to a person who buys insurance (in general) because it gives her/him peace of mind. Our probit model results (Table 2) shows that these individuals are significantly more likely to purchase flood insurance.

The results of the previous models show that when we control for relevant independent variables that influence flood insurance purchases, a consistent positive relation between flood insurance and the implementation of ex ante risk reduction measures is found. For households in our sample, insurance and risk reduction measures are complements. As a robustness check, we also estimate models Footnote 17 with the number of implemented emergency preparedness or risk reduction measures as dependent variable and mandatory and voluntary purchases as explanatory variables along with other control variables noted in Tables 1 and 2. The results of these alternative models, reported in ESM Tables 3 and 4, reveal the same relationships between the flood damage mitigation measures as those in Tables 1 and 2. That is, insurance and emergency preparedness measures are substitutes, while insurance and risk reduction measures are complements.

Next we examine whether the aforementioned behavioral variables that were found to influence voluntary flood insurance purchases in Table 2, directly influence the relationship between insurance purchases and the implementation of risk reduction measures by adding interaction terms with the risk reduction variable. Footnote 18 In particular, the left column of Table 3 shows a model with interactions terms of behavioral characteristics. We examined a model that included interactions of the risk reduction measures variable with peace of mind, the threshold level of concern, the private value of preparing for floods and external locus of control. The interactions of risk reduction with peace of mind and the threshold level of concern are insignificant (not shown here) and model fit is better when these variables are included independently, as is done in the model in Table 3.

The interaction term risk reduction measures × strong private value of preparing for floods is significant at the 5% level. The positive sign implies that individuals with a high private value to prepare for flooding are more likely to take both risk reduction measures and purchase flood insurance. The negative marginal effect of the interaction risk reduction measures × external locus of control suggests that individuals with an external locus of control are less likely to take both flood insurance and ex ante risk reduction measures, but this effect is only weakly significant (p value = 0.08).

The right column of Table 3 shows a model that adds interaction terms of the risk reduction measures variable with variables of important financial incentives for implementing both ex ante risk reduction measures and purchasing flood insurance, which are the flood damage the respondent suffered in the past and whether or not s/he received federal disaster assistance. The main results of the previous model remain similar. Additional insights of this model are that the interaction risk reduction measures × experienced flood damage is highly significant and positive. This suggests that individuals who experienced severe flood damage in the past are more likely to take both flood insurance and ex ante flood-proofing measures. This observation can reflect availability bias, which implies that individuals who experienced severe flood damage in the past find it easy to imagine this could occur again in the future and, therefore, prepare well for flooding. Moreover, a reason for this may be that insurance reimbursements for flood damage in the past were insufficient, which is why insured individuals also take flood damage mitigation measures. As an illustration, our respondents who received compensation for flood damage they experienced in the past indicate that the amount of compensation they received was on average only about 45% of the total damage they suffered to their building and home contents. This past high level of uncompensated flood damage by insurance can also reconcile our finding in Table 3 that past flood damage influences the decision to both purchase insurance and take risk reduction measures with the previous result that past flood damage did not significantly influence the purchases of flood insurance independently. Taking both insurance and risk reduction measures for the uncovered risk may be seen as an effective strategy to deal with high flood damage by our respondents.

The negative significant marginal effect of the variable risk reduction measures × received disaster assistance implies that individuals who have received federal disaster assistance for flood damage in the past are less likely to both take flood insurance and ex ante risk reduction measures.

Conclusions

While the economics literature often assumes that insurance purchase and adoption of preventive measures are substitutes, several empirical studies on the purchase of health-related insurance, have shown this is not the case. Explanations put forward for those findings are that individuals select into buying insurance based on risk preferences which also cause them to undertake other risk reduction measures. We offer an examination of this behavior in the context of low-probability/high-impact disaster risks, specifically, floods. We focused on floods since they have caused hundreds of billions of dollars losses in the United States alone over the last decades and have also affected more people and caused more economic losses worldwide than any other natural disaster (CRED 2015). With the growing concentration of population and assets in flood prone areas in a number of countries, this risk is likely to become an even more important issue in the years to come.

The overall pattern of results shows that long before individuals are faced with a threat of experiencing a loss from flooding they are likely to both have flood insurance and take risk reduction measures in their home to limit future flood damage. This behavior implies preferred risk selection, thus supporting H2 rather than H1 (that suggests that the relationship between insurance and risk reduction was negative; i.e. they are substitutes). With respect to emergency preparedness, insured individuals are less likely to take measures to limit damage than uninsured individuals, behavior which supports H1 and implies a moral hazard problem. These findings indicate that the nature and timing of the protection measure adoption should be more closely considered than has been so far in previous studies. Our statistical models reveal that purchasing flood insurance is negatively related to obtaining federal disaster assistance, an illustration of charity hazard.

We have extended the usual economic model to test how a variety of behavioral mechanisms can explain flood insurance demand: that is the case for peace of mind, having an external locus of control which implies that individuals expect to have little influence over the risks they face, and having a strong private value of preparing for flood. The positive relationship we find for the latter variable is consistent with previous findings that private values are a stronger predictor than social norms in the context of recycling decisions (Viscusi et al. 2011; Huber et al. 2017). Individuals who purchase flood insurance and flood-proof their building exhibit private values of preparing for floods and experienced high amounts of flood damage in the past. Individuals who received federal disaster assistance in the past are less likely to both purchase insurance and take risk reduction measures. The lack of locus of control about life in general has a negative impact on flood insurance demand.

The NFIP has been facing problems with a low up take of coverage and increasing flood losses that caused large deficits in the program; the NFIP is undergoing reforms Footnote 19 to address these issues. Several of our findings are relevant for these reforms. Our finding of a negative relationship between purchasing flood insurance and undertaking emergency preparedness implies that financial incentives or regulations are needed to encourage insured people to invest in these measures. For instance, it has been proposed that offering premium discounts to policyholders who reduce their risk can stimulate individuals to better prepare for flooding. Even though we find that risk reduction measures and insurance can be complements, there is a large group of people who do not take these measures for which such financial incentives to encourage risk reduction may also be relevant. Moreover, we find low income to significantly limit insurance purchase. This suggests that addressing affordability should be given attention in efforts of the NFIP to increase the market penetration of flood insurance. The finding that federal disaster assistance crowds out private flood risk reduction and insurance demand suggests that individual flood preparedness can be improved by limiting federal disaster relief, or by offering alternative forms of relief, like loans instead of grants.

Our findings that behavioral characteristics, such as locus of control and private values, influence flood insurance purchases as well as the joint decision to mitigate risk, opens up avenues for further research to study how these may be activated to stimulate flood preparedness such as using information campaigns.

Notes

-

Over the period 1953–2011, two-thirds of all presidentially declared disasters were flood related (Michel-Kerjan and Kunreuther 2011).

-

Part of this survey data has been used in previous studies that focused on examining determinants of flood risk perceptions (Botzen et al. 2015) and assessing the role of political affiliation in flood risk perceptions and demand for risk mitigation (Botzen et al. 2016). The latter study showed that political affiliation is not a significant determinant of flood insurance purchases, and hence this variable is not further considered here.

-

For this sub-group of people who have not purchased flood insurance (Y i = 0) we cannot make a distinction between people who violate the law because they should have purchased flood insurance and people who do not violate the law by not being insured against flood risk.

-

As an illustration, the simple models 1 for mandatory flood insurance purchases and 2 for voluntary flood insurance purchases are based on 800 and 559 observations (N), respectively, which reflects the size of the sub-samples used by these models. The N for models 3a and 3b for mandatory purchases drop to 520 and 507, respectively, and the N for models 4a and 4b for voluntary purchases drop to 331 and 336, respectively (Table 1). The declining N is mainly caused by missing observations for income, and the risk perception and expert estimates of risk variables. N in model 5 for voluntary purchases increases to 363 (Table 2), because of fewer missing observations of the behavioral variables in that model compared with the risk perception and expert estimates of risk variables. It should be noted that our main relations of interest between flood insurance purchases and risk reduction activities are similar in all models, and hence are robust to these changes in N.

-

The external locus of control variable is defined by responses to the question "Some people feel they have completely control over their lives, while other people feel that what they do has no real effect on what happens to them. Please indicate on a scale from 1 to 10 where 1 means "none at all" and 10 means "a great deal" how much control you feel you have over the way your life turns out." which is based on the U.S. World Values Survey (see ESM). The dummy variable of an external locus of control equals 1 if the respondent answered 1 through 5 on this scale and 0 otherwise.

-

See ESM for examples of social norms and private values in the context of the flood preparedness.

-

The private value was measured using the question "Please tell me if you strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree or strongly disagree with the following statement: I would be upset if I noticed that someone who got flooded was insufficiently prepared for flooding and needed to request federal compensation for flood damage he suffered." For eliciting the social norm, the text was: "Other people would be upset if they noticed that someone who got flooded was insufficiently prepared for flooding and needed to request federal compensation for flood damage he suffered" (see ESM). The private value and social norm variables take on the value 1 if the respondent agreed or strongly agreed with the statement and zero otherwise.

-

About 16% of the respondents without flood insurance indicated that they have elevated their home above potential flood levels. This percentage is the same for respondents with mandatory flood insurance coverage and is 15% for households who purchased flood insurance voluntarily. An evaluation of the NFIP concluded that the discounts are not high enough (Jones et al. 2006), which may explain why people with NFIP coverage are not more likely to elevate their house than people without coverage.

-

This sign change is not caused by multi-collinearity. The correlation between these two variables is only 0.31. In general we checked all correlation coefficients of explanatory variables in all of our models to make sure they are not too high and problems with multi-collinearity do not occur.

-

The perceived flood probability is measured as a dummy variable of respondents who expect that their flood probability is higher than 1/100. The main results are similar if instead this variable is specified as a continuous variable of the respondent's best estimate of the flood probability, which is not included in the reported model in Table 1 because of its large number of missing observations (N drops to 169 for voluntary purchases).

-

This variable is measured as the absolute value of expected flood damage. In addition we estimated a model with a variable of the expected flood damage relative to the respondent's property value as an explanatory variable, which is an indicator of perceived severity of flooding and resulted in similar main findings. In other words, our main results are robust to this alternative specification.

-

The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is charged with mapping flood risk in hazard prone areas and releasing this information to the public. Different FEMA flood zones correspond to different level of risk. Usually high risk areas are defined as those where there is a higher-than 1% chance of being flooding in any given year. Also, the publicly available FEMA flood zone classifications do not have a significant influence on voluntary flood insurance purchases (results not shown in Table 1). This may not be surprising since the accuracy of the NYC FEMA flood zone classification has been highly debated (Aerts et al. 2013).

-

About 37% of the respondents received federal disaster assistance for flood damage they experienced in the past. The average federal disaster compensation received was $21,908 which is substantial, but lower than the average compensation of $34,766 that respondents with flood coverage received in insurance payments.

-

Respondent's age and gender are not statistically significant (results not shown in Table 1).

-

We examined the influence of flood experience by testing different models with the following indicators of flood experience: a dummy variable of whether a respondent experienced flooding in the past (=1) or not (=0), a variable of the number of times a respondent has been flooded, and a variable of the damage the respondent suffered from the last flood event. These variables were statistically insignificant and have been excluded from the model in Table 2. It should be noted that the main relations between flood insurance purchases and implementation of damage mitigation measures remain similar in these models that control for flood experience.

-

We examined whether individuals are more likely to have a strong private value for flood protection when they received federal disaster assistance in the past or experienced high flood damage, and found that these relations are statistically insignificant.

-

Poisson regression models are used for these analyses, because the dependent variables of the number of implemented emergency preparedness and risk reduction measures are count variables.

-

These variables are included only as interaction terms and not separately to prevent potential problems with multicollinearity. Correlation statistics of these separate variables with the interaction term are about 0.7.

-

Examples of these reforms are the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012, the Homeowners Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014, and the Flood Insurance Market Parity and Modernization Act of 2016.

References

-

Aerts, J. C. J. H., & Botzen, W. J. W. (2011). Climate-resilient waterfront development in New York City: Bridging flood insurance, building codes, and flood zoning. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1227, 1–82.

-

Aerts, J. C. J. H., Lin, N., Botzen, W. J. W., Emanuel, K., & de Moel, H. (2013). Low probability flood-risk modeling for New York City. Risk Analysis, 33(5), 772–788.

-

Aerts, J. C. J. H., Botzen, W. J. W., Emanuel, K., Lin, N., de Moel, H., & Michel-Kerjan, E. (2014). Evaluating flood resilience strategies for coastal mega-cities. Science, 344, 473–475.

-

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for 'lemons': Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84, 488–500.

-

Arnott, R. J., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1988). The basic analytics of moral hazard. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 90, 383–413.

-

Barberis, N. (2013). The psychology of tail events: Progress and challenges. The American Economic Review, 103(3), 611–616.

-

Baumann, D. D., & Sims, J. H. (1978). Flood insurance: Some determinants of adoption. Economic Geography, 54, 189–196.

-

Botzen, W. J. W., Kunreuther, H., & Michel-Kerjan, E. (2015). Divergence between individual perceptions and objective indicators of tail risks: Evidence from floodplain residents in New York City. Judgment and Decision making, 10(4), 365–385.

-

Botzen, W. J. W., Michel-Kerjan, E., Kunreuther, H., de Moel, H., & Aerts, J. C. J. H. (2016). Political affiliation affects adaptation to climate risks: Evidence from New York City. Climatic Change, 138(1), 353–360.

-

Browne, M. J., & Hoyt, R. E. (2000). The demand for flood insurance: Empirical evidence. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 20(3), 291–306.

-

Buchanan, J. (1975). The Samaritan's dilemma. In E. Phelps (Ed.), Altruism, morality, and economic theory (pp. 71–85). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

-

Carson, J. M., McCullough, K. A., & Pooser, D. M. (2013). Deciding whether to invest in mitigation measures: Evidence from Florida. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 80(2), 309–327.

-

Chiteji, N. (2010). Time preference, noncognitive skills and well being across the life course: Do noncognitive skills encourage healthy behavior? American Economic Review, 100, 200–204.

-

Cohen, A., & Siegelman, P. (2010). Testing for adverse selection in insurance markets. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 77, 39–84.

-

Coleman, M., & Deleire, T. (2003). An economic model of locus of control and the human capital investment decision. Journal of Human Resources, 38, 701–721.

-

CRED. (2015). The human costs of natural disasters: A global perspective. Belgium: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED).

-

Cutler, D. M., Finkelstein, A., & McGarry, K. (2008). Preference heterogeneity and insurance markets: Explaining a puzzle of insurance. American Economic Review, 98, 157–162.

-

de Meza, D., & Webb, D. C. (2001). Advantageous selection in insurance markets. The Rand Journal of Economics, 32, 249–267.

-

Dehring, C. A., & Halek, M. (2013). Coastal building codes and hurricane damage. Land Economics, 89(4), 597–613.

-

Ehrlich, I., & Becker, G. S. (1972). Market insurance, self-insurance, and self-protection. The Journal of Political Economy, 80, 623–648.

-

Einav, L., Finkelstein, A., Ryan, S. P., Schrimpf, P., & Cullen, M. R. (2013). Selection on moral hazard in health insurance. American Economic Review, 103, 178–219.

-

Elster, J. (1989). Social norms and economic theory. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4, 99–117.

-

Evans, D. S., & Leighton, L. S. (1989). Some empirical aspects of entrepreneurship. American Economic Review, 79(3), 519–535.

-

Finkelstein, A., & McGarry, K. (2006). Multiple dimensions of private information: Evidence from the long-term care insurance market. American Economic Review, 96, 938–958.

-

Heineck, G., & Anger, S. (2010). The returns to cognitive abilities and personality traits in Germany. Labour Economics, 17, 535–546.

-

Huber, J., Viscusi, W. K., & Bell, J. (2017). Dynamic relationships between social norms and pro-environmental behavior: Evidence from household recycling. Behavioural Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2017.13.

-

Hudson, P., Botzen, W. J. W., Czajkowski, J., & Kreibich, H. (2017). Moral hazard in natural disaster insurance markets: Empirical evidence from Germany and the United States. Land Economics, 93(2), 179–208.

-

IPCC. (2014). Climate change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

-

Jones, C. P., Coulborne, W. L., Marshall, J., & Rogers, S. M. (2006). Evaluation of the National Flood Insurance Program's building standards (pp. 1–118). Washington D.C.: American Institutes for Research.

-

Kousky, C., & Kunreuther, H. C. (2014). Addressing affordability in the National Flood Insurance Program. Journal of Extreme Events, 1(1), 450001.

-

Kousky, C., Michel-Kerjan, E.O., & Raschky, P.A. (2013). Does federal disaster assistance crowd out private demand for insurance? Working Paper 2013–10. Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

-

Krantz, D. H., & Kunreuther, H. C. (2007). Goals and plans in decision making. Judgment and Decision making, 2(3), 137–168.

-

Kunreuther, H. C., Novemsky, N., & Kahneman, D. (2001). Making low probabilities useful. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 23(2), 161–186.

-

Lin, N., Emanuel, K., Oppenheimer, M., & Vanmarcke, E. (2012). Physically based assessment of hurricane surge threat under climate change. Nature Climate Change, 1389, 462–467.

-

Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K., & Welch, N. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 267–286.

-

McClelland, G., Schulze, W., & Coursey, D. (1993). Insurance for low-probability hazards: A bimodal response to unlikely events. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 7, 95–116.

-

Michel-Kerjan, E., & Kunreuther, H. (2011). Redesigning flood insurance. Science, 433, 408–409.

-

Munich Re. (2015). Loss events worldwide 1980–2014. Munich Re: NATCATSERVICE.

-

Petrolia, D. R., Hwang, J., Landry, C. E., & Coble, K. H. (2015). Wind insurance and mitigation in the coastal zone. Land Economics, 91(2), 272–295.

-

Raschky, P., Schwarze, R., Schwindt, M., & Zahn, F. (2013). Uncertainty of governmental relief and the crowding out of flood insurance. Environmental and Resource Economics, 54(2), 179–200.

-

Rothschild, M., & Stiglitz, J. (1976). Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: An essay on the economics of imperfect information. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 90(4), 630–649.

-

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28.

-

Sattler, D. N., Kaiser, C. F., & Hittner, J. B. (2000). Disaster preparedness: Relationships among prior experience, personal characteristics, and distress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(7), 1396–1420.

-

Savage, L. J. (1954). The foundations of statistics. New York: Wiley.

-

Slovic, P., Fischhoff, B., Lichtenstein, S., Corrigan, B., & Combs, B. (1977). Preference for insuring against probable small losses: Insurance implications. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 44(2), 237–258.

-

Thieken, A. H., Petrow, T., Kreibich, H., & Merz, B. (2006). Insurability and mitigation of flood losses in private households in Germany. Risk Analysis, 26, 383–395.

-

Viscusi, W. K., Huber, J., & Bell, J. (2011). Promoting recycling: Private values, social norms, and economic incentives. American Economic Review, 101(3), 65–70.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kerr and Downs Research for help with designing and implementing the survey. This research has received financial support from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), the Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes Center, and the Travelers/Wharton Partnership for Risk Management. Moreover, this research received support from NYC‐DCP, NYC‐Mayor's Office/OLTPS, NYC‐DOB, NYC‐OEM, and the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) grant EAR‐1520683.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Botzen, W.J.W., Kunreuther, H. & Michel-Kerjan, E. Protecting against disaster risks: Why insurance and prevention may be complements. J Risk Uncertain 59, 151–169 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-019-09312-6

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-019-09312-6

Keywords

- Adverse selection

- Charity hazard

- Decision making under risk

- Flood insurance

- Moral hazard

- Risk perception

JEL classification

- Q54

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11166-019-09312-6